Are you spiritual? Religious? Not sure? As a hospital chaplain, these are confusions that I deal with everytime I walk into a patient’s room for the first time.

My presence is sometimes met with an admission: “I’m not religious”. Or it can be a sheepish confession: “I haven’t been to church/temple/mosque in a while.”

I hear it enough that I’ve come up with a retort to put them at ease: “That’s ok, I’m not that religious today either!”

While this usually elicits a confused chuckle, my hope is to convey that the goal is not religiosity. As a chaplain and spiritual director, I’m not interested in their religious report card. I’m interested in how it is with their spirit.

Bella was a patient I met through a similar introduction. A former actress in her fifties, her wavy hair had a brassy red hue that matched her personality. She told me that she hadn’t been to church in years, but she was bored so she might as well talk to me.

“I don’t really care about faith and all that junk,” she admitted.

“What is it that you do care about?” I asked.

Without missing a beat, she declared, “My family.”

Even though I didn’t tell her this, Bella was expressing a deep belief in something. She was defining what theologian Paul Tillich would say is her “ultimate concern.”

For Tillich, an ultimate concern is what gives meaning to life and should be the focus of one’s entire being. It transcends all other concerns, becoming the criterion by which all other aspects of life are judged. This is not limited to religious belief but can encompass any deeply held value or priority that shapes one's understanding of the world.

This is exactly what Bella was describing.

In the 40 minutes that followed, Bella shared with me about her ultimate concern.

She worried about her mother and felt guilty about not being able to take care of her from the hospital. With glee, she showed me pictures of her nephews. Through tears, she spoke of her grief of never having children of her own. She told me about her brother who had died a few years earlier and how much she missed him.

As she contemplated her own mortality in the face of a cancer diagnosis, I asked what she feared most. She thought for a moment and whispered, “I don’t want to feel alone.”

Bella may not have had a label that she was comfortable using to describe her ultimate concerns. And who could blame her? “Religion”1 comes with a lot of baggage. It can be tied to the complexities of one’s upbringing, institutional harm and potential toxicity, just to name a few problematic dynamics.

Many try to avoid the baggage altogether by coming up with their own understanding of being “spiritual but not religious”. Others don’t like the term “spiritual”, claiming that it is too individualistic, new-agey, or has been commoditized. People want to convey that they have ultimate concerns, but the traditional language and labels have become too fraught.

When we try to figure out if we are spiritual and/or religious, we are not all on the same page, given our individual experiences and opinions.

It is confusing.

There is much (sometimes heated) debate around spirituality and religion. Can one be spiritual and not religious? Or religious and not spiritual? How are the two related? Is one dependent on the other? It doesn’t help that we don’t have universal definitions for either spirituality or religion. Here is my very basic delineation:

Religion: An agreed upon set of rituals, practices and beliefs held by a community for the sake of communing with the divine.

Spirituality: How you connect to and explore the world within and around you. How you make meaning and find transcendence.

These are simple definitions that encapsulate the distinction between the two modes. For some, religion can be a source of spirituality; for others, spirituality is accessible without the need of religion.

Religion and Spirituality researchers (who are far more adept at discussing this than I am) collapse the two definitions into one, writing,

“Spirituality is the personal quest for understanding answers to ultimate questions about life, about meaning, and about relationship to the sacred or transcendent, which may (or may not) lead to or arise from the development of religious rituals and the formation of community”2

This reminds me of how a rabbi friend of mine likes to phrase it, “Spirituality is the map; religion can be one route someone takes, but there can be lots of paths to get where you are going.”

While labels shouldn’t matter (it should be more about the wine!) They can be helpful distinctions when we are looking at demographics, trends and research.

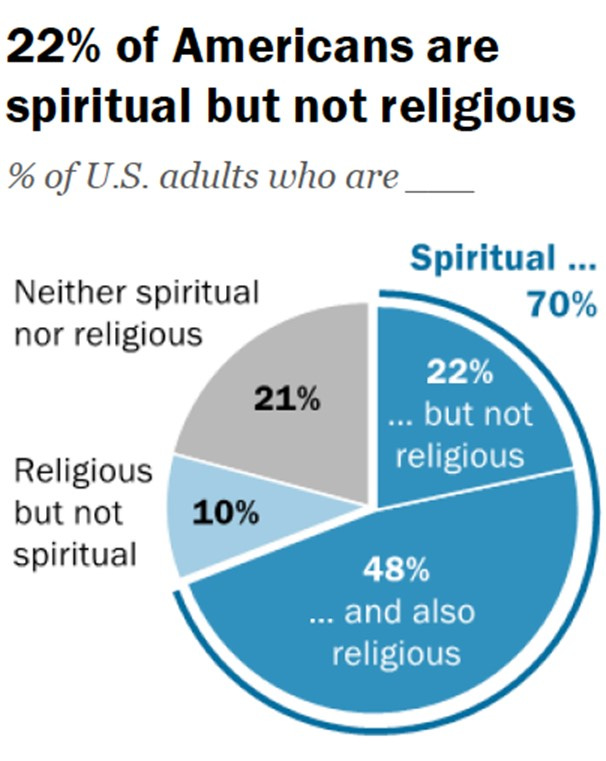

In my world, we often use the shorthand SNR in our categorizations – Spiritual Not Religious. The Pew Research Center, in their most recent 2023 study found that 7 out of 10 adults in the United States consider themselves “spiritual” with 22% of those identifying as spiritual not religious.

(For a deeper dive into the recent statistics and data around this, I recommend the following substack from )

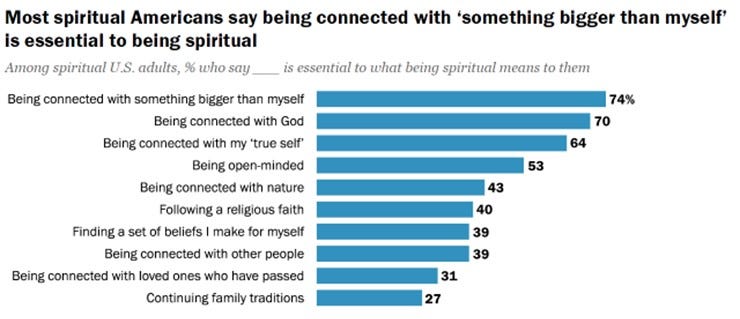

As a society we will continue to disentangle and redefine what it means to be spiritual. I found the findings from the Pew study below compelling of how people responded when asked what being spiritual means to them?

How would you answer this question? Do you see your own sense of being spiritual represented here?

Some of us have no problem labeling ourselves with traditional terminology. Some of us change our labels as frequently as we change our clothes. Some of us are still confused and chafe at the idea of defining our beliefs so concretely.

This is part of why chaplains and spiritual directors can play such a vital role. We are trying to meet people wherever they are, using (or not using) whatever labels make sense for them. The box that you check (or don’t check) doesn’t matter as much as how you define your ultimate concerns and how they guide your life.

What tends to matter most to those I journey alongside, is being able to name and honor those ultimate concerns. To be given the space to be held as the beautifully complex beings they are, beyond any boxes.

What are your ultimate concerns?

How would you define religion and spirituality?

Do you claim a label for yourself?

Do you see yourself in the data?

Within the field of chaplaincy and larger academic contexts, there is a move away from referring to someone’s religion and instead using the term “spiritual/values based orienting system” as it is more inclusive of where people are and how they might define themselves. For the purposes of brevity and common language, we will just use “religion” here.

Koenig H. G., McCullough M. E., Larson D. B. (2001). Handbook of Religion and Health.1st ed. eds. Koenig H. G., McCullough M. E., Larson D. B. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Thought provoking. I believe I’m more spiritual than religious. I heard in a meeting once: Religion is for people who don’t want to go to hell; spirituality is for those who’ve already been there. 🙏

This is a very helpful piece! Thank you. As you might guess, I'm both/and.