I once heard a story about a philosopher who was teaching in the West. He asked his students, “What is the opposite of death?” Without hesitation, the class responded in unison, “Life.” Later, this same philosopher posed the question to a group of students in the East. This time, the answer was different; they replied, “Birth.”

Our society has set up a dichotomy around death that makes it the opposite of life. Death is a topic of conversation to be avoided rather than a natural part of the human process. We actively try to sanitize death and keep it out of sight. When the concept of our finitude does arise, we often try to tip-toe around it or push it out of our minds. It is not something we like to think about, let alone talk about with others.

I know it can be sad and morbid to think about dying, but it doesn’t have to be just those things. Contemplating death can also be transformative. It can sharpen our perspective, increase our gratitude and expand our compassion. If we are aware of our own mortality then we can live a deeper, more wholehearted life.

Until we accept death as inevitable, we cannot fully live.

The Danger of Denial

It’s a matter of when we will die, not if.

When I was training to be a chaplain educator, I watched as my supervisor at the time asked a group of clergy when they thought they might die. At first, I was surprised by his question and then I was shocked by their answers. They were all Christian pastors and happened to be in complete denial. They started listing ages of 106, 114, 121 etc.

If we are out of touch with reality, we cannot appreciate this life for the brief gift that it is and respond accordingly. We run the risk of taking life for granted and then missing out on the preciousness of it.

One day I was in the Emergency Department with a patient who did live to 106 years old. Her son and daughter had just been told by the physician that she was about to die.

When I walked in the room, the family was apoplectic. As they touted their mother’s “perfect health,” they became obsessed with the notion that the hospital had done something wrong. They were in the hallway trying to call malpractice attorneys while their mother took her last breath. Their denial cost them the last moments of their mother’s life.

Later, the son confided “It never occurred to me that she would die one day.” While grief and shock can impact people differently, they were suffering two huge losses at the same time – grieving for their mother and for the concept of mortality in general.

Rather than deny the reality of our own or loved one’s eventual demise – if we can acknowledge it before it happens, it can have a healing and liberating effect.

Monk and Author Thich Nhat Hanh has said, “It’s not impermanence that makes us suffer. What makes us suffer is wanting things to be permanent when they are not.”

Let’s embrace our impermanence as a spiritual practice to both lessen our suffering and deepen our lives.

The Benefits of Befriending our Impermanence

We don’t have to be saying goodbye to a loved one or suffering a terminal illness to contemplate our death. If we ponder death while we are hearty and hale, it can have numerous spiritual benefits.

Confronting Mortality

The clinical term for an imminent death in the hospital is “actively dying.” This is a phrase I use all day long as we often have to triage multiple requests and determine how quickly we need to respond to various patient encounters. One day I was taking a referral over the phone from a nurse and asked him a routine (for me) question - “Is the patient actively dying?” He responded, “Aren’t we all?”

While at that moment I was not looking for a contemplative approach to our mortality - he was right. Accepting that we all have endings unites humanity. We will all die, some like my patient, that day - but all of us eventually. When we can open our eyes to that reality, we can often see more clearly and not be surprised when it happens to us or those we love.

Living with Purpose

Oliver Burkeman is the author of the book 4,000 Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. The title itself is a wake up-call to the brevity of our lives. He writes,

“The average human lifespan is absurdly, terrifyingly, insultingly short. But that isn’t a reason for unremitting despair, or for living in an anxiety-fueled panic about making the most of your limited time. It’s a cause for relief. You get to give up on something that was always impossible—total control over your life—and relax into the experience of living.”

Recognizing our time here is limited encourages us to take stock of what is truly important. And run toward that.

It brings up important, clarifying and challenging questions like the following:

What do I value most about this world, how do I prioritize that?

How do I want to be remembered, how do I live this way now?

How can I live more fully today, knowing tomorrow is not guaranteed?

How can I express love more freely, knowing I won’t be around forever?

What am I avoiding or delaying in my life, thinking that I have more time?

You may want to ask yourself these difficult questions or journal about them and see what comes up. This is a chance to delve into meaning and live more fully.

Letting Go of Attachments

I once saw a t-shirt that said “He who dies with the most toys wins.” While meant to be tongue in cheek, unfortunately I think this is consistent with our consumerist mentality. Even when we are told we can’t take it with us or not to store up treasures in this world, our attachments can be hard to let go of as we seek to surround ourselves with stuff.

But sometimes the stuff isn’t just material in nature, it can be relationships, anxieties, fears, any number of things that we cling to in the hopes that it will protect us from suffering. Thinking about our impermanence invites us to hold all those things loosely, knowing that in the end, they too will fade away.

This is where we can turn to the Buddhists for help.

Buddhist death meditation, or Maraṇasati, is a practice that encourages individuals to reflect deeply on the reality of death as a natural part of life. It invites individuals to let go of attachments and illusions of permanence, helping them to live with more presence, compassion and wisdom.

You can read more about the practice in Pema Chodron’s book, How We Live is How We Die. Among her many pearls of wisdom, she writes,

“By acknowledging the reality of impermanence, we free ourselves from clinging and grasping, which opens the door to deeper peace.”

Mindfulness of the Present

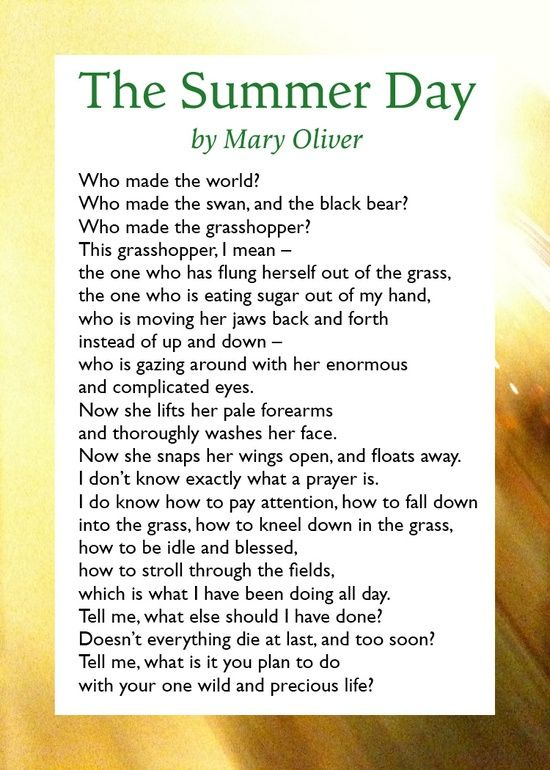

Poet Mary Oliver’s words often surface when reflecting on the sacred fleetingness of life. Her poems remind us of the ephemeral and invite us to consider if or how that knowledge changes us.

Her poem “The Summer Day” speaks to this concept and the season that we’re on the cusp of saying goodbye to.

It is often the last couplet of the poem that is quoted and it is a good one

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

But it’s often taken out of context of the larger poem and put on inspirational signs or mugs as an invitation to “YOLO” – aka engage in adventure because “You Only Live Once.” People quote it as a reminder to do the most things or carpe diem. But it is not just about making the most of the moment with little regard to the future. It is about knowing this life is so very brief and choosing to honor that by communing with nature and noticing the grasshopper.

For me, being present to death daily serves as a reminder to let go of the things that will not matter when looking at my life as a whole. Knowing that tomorrow is not promised helps to appreciate today. Thinking of how I want to be remembered invites me to lean into that legacy now.

My patients have been my teachers about embracing impermanence, and here’s a story about one of them who lives on in my heart.

Hatching, Matching & Dispatching

I was a chaplain intern during the time that hospitals maintained different floors for patients with HIV/AIDS. I was assigned to that unit and surprised that the patients there were so happy to see a chaplain. The patients were incredibly lonely as many people would not visit due to fear, stigma and misinformation about the contagiousness of their illness.

One of the first patients I ever saw, Shirley, was on that unit. She was admitted a few days after I began my 10 week summer internship and died the week before I left.

When I first introduced myself to Shirley, she threw her arms up in the air and demanded “yes, sit down, I have so much to talk with you about!”

Indeed, she did, and we spent many afternoons that summer engaging in what I would later learn is called “Life Review”—an intentional conversation reflecting on the highs and lows of one’s life, all the major events that had occurred, all the sorrows, regrets, and celebrations. Shirley insisted on calling me “my Pastor,” although it came out as “my Pasta” in her thick New York accent. I told her that I wasn’t allowed to be called that, as I was still in seminary and not yet ordained. She didn’t care. She was a lifelong member of her church, but her own “Pasta” never visited. She told me she was “hatched, matched and ready to be dispatched” in the same church. I had no idea what she was talking about and she spelled it out for me: “hatched - I was baptized there as a baby; matched - I was married to my husband; and dispatched - what they are going to do at my funeral when I am ready.”

I tentatively asked Shirley about how she felt about that last part of the rhyme. “I’m ready, Pasta. I’ve been in pain for so long. It’s been lonely without my husband (who died of heart failure years earlier). I’m eager to see him again. My kids are all grown and they will be fine without me. They’re sad, so I can’t tell them that I’m not afraid because they tell me to keep fighting.”

Shirley was the first patient I ever spoke to about her impending death and she taught me what it means to have total acceptance. It was only later that I realized how rare acceptance that is for most people. She faced the end of her life with clarity and peace. In the stories she shared with me over the next two months, we laughed and cried together about all she had been through. I wasn’t at the hospital when she died one night. Her son called me the next day and told me, “My mom told me I had to tell you, her pastor, thank you for three things: your company, your understanding and helping her get ready to be dispatched. I don’t know what that last one means, but she made me underline it and said you’d know.”

Our lives start with hatching, we may encounter some matching and we will all end with dispatching. We can learn from Shirley that accepting all of these life cycle phases can help us find meaning and peace.

Wonderful post. So much wisdom

I am so moved by this piece Christine! Not an easy subject to talk about and yet it's so important and universal. This is a topic I reflect on a lot in my own writing. One of the things that surprised me most about grief is how it shifted my entire perspective on life - being confronted with the impermanence of life, while scary, has the power to inspire us to live with intention and make the most of the time we are given. You've done a brilliant job distilling the key points in a way that is deeply heartfelt and incredibly practical!